NASA's senior leaders in human spaceflight gathered for a momentous meeting at the agency's headquarters in Washington, DC, almost exactly ten years ago.

These were the people who, for decades, had developed and flown the Space Shuttle. They oversaw the construction of the International Space Station. Now, with the shuttle's retirement, these princely figures in the human spaceflight community were tasked with selecting a replacement vehicle to send astronauts to the orbiting laboratory.

Boeing was the easy favorite. The majority of engineers and other participants in the meeting argued that Boeing alone should win a contract worth billions of dollars to develop a crew capsule. Only toward the end did a few voices speak up in favor of a second contender, SpaceX. At the meeting's conclusion, NASA's chief of human spaceflight at the time, William Gerstenmaier, decided to hold off on making a final decision.

A few months later, NASA publicly announced its choice. Boeing would receive $4.2 billion to develop a "commercial crew" transportation system, and SpaceX would get $2.6 billion. It was not a total victory for Boeing, which had lobbied hard to win all of the funding. But the company still walked away with nearly two-thirds of the money and the widespread presumption that it would easily beat SpaceX to the space station.

The sense of triumph would prove to be fleeting. Boeing decisively lost the commercial crew space race, and it proved to be a very costly affair.

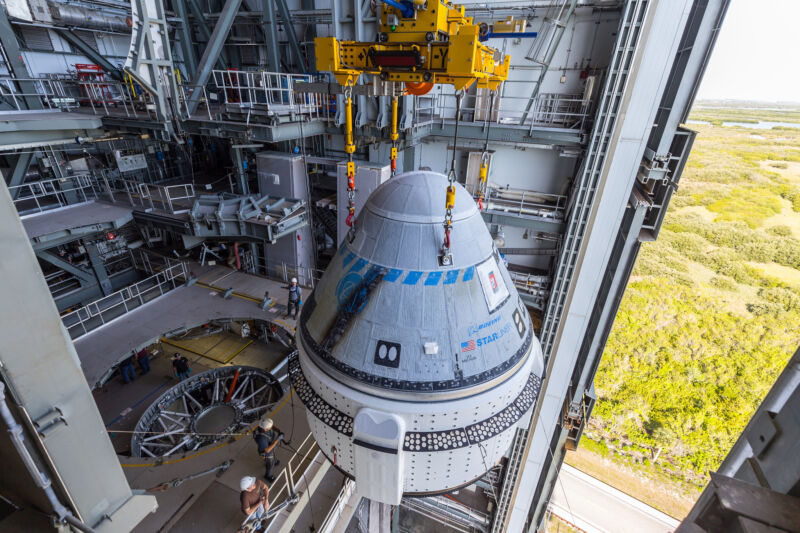

With Boeing's Starliner spacecraft finally due to take flight this week with astronauts on board, we know the extent of the loss, both in time and money. Dragon first carried people to the space station nearly four years ago. In that span, the Crew Dragon vehicle has flown thirteen public and private missions to orbit. Because of this success, Dragon will end up flying 14 operational missions to the station for NASA, earning a tidy fee each time, compared to just six for Starliner. Through last year, Boeing has taken $1.5 billion in charges due to delays and overruns with its spacecraft development.

AdvertisementSo what happened? How did Boeing, the gold standard in human spaceflight for decades, fall so far behind on crew? This story, based largely on interviews with unnamed current and former employees of Boeing and contractors who worked on Starliner, attempts to provide some answers.

The early days

When the contracts were awarded, SpaceX had the benefit of working with NASA to develop a cargo variant of Dragon, which by 2014 was flying regular missions to the space station. But the company had no experience with human spaceflight. Boeing, by contrast, had decades of spaceflight experience, but it had to start from scratch with Starliner.

Each faced a deeper cultural challenge. A decade ago, SpaceX was deep into several major projects, including developing a new version of the Falcon 9 rocket, flying more frequently, experimenting with landing and reuse, and doing cargo supply missions. This new contract meant more money but a lot more work. A NASA engineer who worked closely with both SpaceX and Boeing in this time frame recalls visiting SpaceX and the atmosphere being something like a frenzied graduate school, where all of the employees were being pulled in different directions. Getting engineers to focus on Crew Dragon was difficult.

But at least SpaceX was in its natural environment. Boeing's space division had never won a large fixed-price contract. Its leaders were used to operating in a cost-plus environment, in which Boeing could bill the government for all of its expenses and earn a fee. Cost overruns and delays were not the company's problem—they were NASA's. Now Boeing had to deliver a flyable spacecraft for a firm, fixed price.

Boeing struggled to adjust to this environment. When it came to complicated space projects, Boeing was used to spending other people's money. Now, every penny spent on Starliner meant one less penny in profit (or, ultimately, greater losses). This meant that Boeing allocated fewer resources to Starliner than it needed to thrive.

"The difference between the two company’s cultures, design philosophies, and decision-making structures allowed SpaceX to excel in a fixed-price environment, where Boeing stumbled, even after receiving significantly more funding," said Lori Garver in an interview. She was deputy administrator of NASA from 2009 to 2013 during the formative years of the commercial crew program and is the author of Escaping Gravity.

So Boeing faced financial pressure from the beginning. At the same time, it was confronting major technical challenges. Building a human spacecraft is very difficult. Some of the biggest hurdles would be flight software and propulsion.

Struggling with software

There was no single flight software team at Boeing. The responsibilities were spread out. A team at Kennedy Space Center in Florida handled the ground systems software, which kept Starliner healthy during ground tests and the countdown until the final minutes before liftoff. Separately, a team at Boeing's facilities in Houston near Johnson Space Center managed the flight software for when the vehicle took off.

Neither team trusted one another, however. When the ground software team would visit their colleagues in Texas, and vice versa, the interactions were limited. The two teams ended up operating mostly in silos, not really sharing their work with one another. The Florida software team came to believe that the Texas team working on flight software had fallen behind but didn't want to acknowledge it. (A Boeing spokesperson denied there was any such friction).

In a fixed-price contract, a company gets paid when it achieves certain milestones. Complete a software review? Earn a payment. Prove to NASA that you've built a spacecraft component you said you would? Earn a payment. This kind of contract structure naturally incentivized managers to reach milestones.

The problem is that while a company might do something that unlocks a payment, the underlying work may not actually be complete. It's a bit like students copying homework assignments throughout the semester. They get good grades but haven't done all of the learning necessary to understand the material. This is only discovered during a final exam, in class. Essentially, then, Boeing kept carrying technical debt forward so that additional work was lumped onto the final milestones.

Ultimately, the flight software team faced a reckoning during the initial test flight of Starliner in December 2019.

OFT-1 misses the mark

This uncrewed flight test faced problems almost immediately after liftoff. Due to a software error, the spacecraft captured the wrong "mission elapsed time" from its Atlas V launch vehicle—it was supposed to pick up this time during the terminal phase of the countdown, but instead, it grabbed data 11 hours off of the correct time. This led to a delayed push to reach orbit and caused the vehicle's thrusters to expend too much fuel. As a result, Starliner did not dock with the International Space Station.

AdvertisementThe second error, caught and fixed just a few hours before the vehicle returned to Earth through the atmosphere, was a software mapping error that would have caused thrusters on Starliner's service module to fire incorrectly. This could have caused Starliner's service module and crew capsule to collide. Senior NASA officials would later declare the mission a "high visibility close call," or very nearly a catastrophic failure.

A couple of months after the flight, John Mulholland, a vice president who managed the company's commercial crew program, met with reporters to explain what happened. He acknowledged that the company did not run integrated, end-to-end tests for the whole mission. For example, instead of conducting a software test that encompassed the roughly 48-hour period from launch through docking to the station, Boeing broke the test into chunks. The first chunk ran from launch through the point at which Starliner separated from the second stage of the Atlas V booster.

Mulholland insisted that Boeing did not cut corners and that the lack of an end-to-end test was not due to cost concerns. "It was definitely not a matter of cost," Mulholland said at the time. "Cost has never been in any way a key factor in how we need to test and verify our systems."

Had Boeing run the integrated test, it would have caught the timing error, Mulholland said. The mission likely would have docked with the International Space Station. It's worth noting that some of the people interviewed for this article say NASA should have pressed Boeing harder for such tests but did not, perhaps out of a sense that Boeing was a superior contractor to SpaceX.

The bottom line is that Boeing technically earned the flight software milestones in its commercial crew contract. But by not putting in the work for an end-to-end test of its software, the company failed its final exam. As a result, Boeing had to take the disastrously expensive step of flying a second uncrewed flight test, which it did in May 2022.

Prop problems

The heart of any spacecraft is its propulsion system. For its Dragon spacecraft, SpaceX developed its Draco and SuperDraco thrusters internally. This is consistent with its vertically integrated approach. Boeing took a more traditional path, turning to industry leader Aerojet Rocketdyne for Starliner's various thrusters. In turn, Rocketdyne had its own myriad subcontractors.

One of the big differences between new space companies like SpaceX and traditional space companies is vertical integration. If it works well, developing and building one's own technology is faster, cheaper, and much more efficient. Everyone is also on the same "team" and pulling in the same direction.

By contrast, partnerships between two large aerospace corporations are often cumbersome. Let's say you're a Rocketdyne engineer working on propulsion. If you want to design a widget that connects with the service module, you need to obtain information about the load limits from Boeing. This involves working with a Boeing engineer and a procurement officer. Rocketdyne engineers must then confirm this information. So you design the widget. Then someone else performs a structural analysis. You go through procurement to buy the materials for the part, then have to go through a manufacturing integrator and engineer to find a supplier to build it.

At the end of this process, perhaps a dozen different people in different departments at different companies have touched the part. It adds time and cost, and no one feels ownership of the process. At a new space company, the process can be much simpler: An engineer designs a part and writes a purchase order for the shop to build it.

"As an engineer, you're supposed to solve hard problems, but the structural inefficiency was a huge deal," said one person familiar with this process at Rocketdyne and Boeing.

It also didn't help that Rocketdyne and Boeing had a poor working relationship.

A test anomaly

That relationship was severely strained in June 2018 when the Starliner spacecraft experienced an anomaly during a hot-fire test of its launch abort system. During the test at a NASA facility in White Sands, New Mexico, the vehicle underwent a successful firing. However, due to a design problem, only four of the eight propellant valves closed at the end of the test.

AdvertisementThis resulted in more than 4,000 pounds of toxic monomethylhydrazine propellant being dumped onto the test stand. There was no detonation or explosion, but a huge fireball engulfed the ground support equipment. The anomaly was caused, at least in part, by poor communication between Rocketdyne and Boeing.

"Boeing and Rocketdyne more or less hated one another," one person involved in the test told Ars. "Everyone was in super-defensive mode even before this happened. It had been classified as a risk, but the two sides weren’t talking openly and honestly about it."

What was the source of the animosity? After Boeing selected Rocketdyne, according to sources, it asked for changes to some system specifications. This prompted Rocketdyne to ask for a change order fee, as is customary in government contracts. That infuriated Boeing, which thought it had a partnership with Rocketdyne, but the latter company saw itself as a contractor. As a result, the Boeing and Rocketdyne teams were effectively walled off from one another and did not iterate together toward a more effective propulsion system.

Initially, Boeing kept quiet about the White Sands accident. The company did not even inform the commercial crew astronauts who were training to fly on the vehicle for a few weeks. It made no public comment until Ars reported on the anomaly nearly a month after it happened. (A Boeing spokesperson said the company immediately informed NASA).

Ultimately, the frayed relationship between Boeing and Rocketdyne reared its head publicly during the second half of 2021 when an issue with sticky valves in the propulsion system delayed the second uncrewed test flight. During its communications surrounding this issue, Boeing started to say it was working with its partners, including Aerojet Rocketdyne, to determine the cause of the valve issues. Effectively, this was the equivalent of throwing a supplier under the bus.

Asked directly about turbulence in the Boeing-Rocketdyne partnership, a Boeing spokesperson said, "We have a broad and diverse supply chain." For all of these suppliers, Boeing applies "the same values and expectations of product safety and product quality for our customers."

Boeing’s terrible, horrible, no good, very bad decade

All of Boeing's struggles with Starliner played out against a much larger backdrop of the company's misfortunes with its aviation business. Most notably, in October 2018 and March 2019, two crashes of the company's relatively new jet, the 737 MAX 8, killed 346 people. The jets were grounded for many months.

The institutional failures that led to these twin tragedies are well explained in a book by Peter Robison, Flying Blind. Robison covered Boeing as a reporter during its merger with McDonnell Douglas a quarter of a century ago and described how countless trends since then—stock buybacks, a focus on profits over research and development, importing leadership from McDonnell Douglas, moving away from engineers in key positions to MBAs, and much more led to Boeing's downfall.

It's estimated that, in addition to paying customers and the families of victims, the grounding of the 737 Max for nearly two years cost Boeing $20 billion since 2019. This critical loss of cash came just as Boeing's space division faced crunch time to complete work on Starliner.

There were so many other challenging issues, as well. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020 occurred when Boeing was dealing with the fallout from all the software issues on Starliner's debut flight. Additionally, the pandemic accelerated the retirement of experienced engineers who had brought spaceflight experience from the shuttle program. Boeing's best people were focused on the aircraft crisis, and the experienced space hands were leaving.

So it was all a pretty titanic struggle.

In late April, I asked Mark Nappi, a Boeing vice president and the manager of the company's commercial crew program, what he thought was the biggest challenge Boeing faced in its quest to fly astronauts.

"Design and development is hard, particularly with a human space vehicle," he replied. "There's a number of things that were surprises along the way that we had to overcome. And so I can't pick any one that I would point to. I would say, though, that it certainly made the team very, very strong."

AdvertisementNever doing that again

The Obama White House created the commercial crew program in early 2009, but Congress was reluctant to go along. It didn't see how companies like SpaceX could ever step up and put astronauts into orbit. According to Garver, the key advisor to Obama on space policy at the time, Congressional purse strings didn't really open up for NASA to support private spacecraft until Boeing indicated its willingness to participate. Suddenly, commercial crew became a legitimate program.

Boeing undoubtedly would like to have that decision back. In hindsight, it seems obvious that the strain of operating in a fixed-price environment was the fundamental cause of many of Boeing's struggles with Starliner and similar government procurement programs—so much so that the company's Defense, Space, & Security division is unlikely to participate in fixed-price competitions any longer. In 2023, the company's chief executive said Boeing would "never do them again."

A Boeing spokesperson pushed back on the idea that the company would no longer compete for fixed price contracts. However, the company believes such contracts must be used correctly, for mature products.

"Challenges arise when the fixed price acquisition approach is applied to serious technology development requirements, or when the requirements are not firmly and specifically defined resulting in trades that continue back and forth before a final design baseline is established," the spokesperson said. "A fixed price contract offers little flexibility for solving hard problems that are common in new product and capability development."

There is a great irony in all of this. By bidding on commercial crew, Boeing helped launch the US commercial space industry. But in the coming years, its space division is likely to be swallowed by younger companies that can bid less, deliver more, and act more expeditiously.

The surprise is not that Boeing lost to a more nimble competitor in the commercial space race. The surprise is that this lumbering company made it at all. For that, we should celebrate Starliner’s impending launch and the thousands of engineers and technicians who made it happen.