Signs point to Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X Elite processors showing up in actual, real-world, human-purchasable computers in the next couple of months after years of speculation and another year or so of hype.

For those who haven’t been following along, this will allegedly be Qualcomm’s first Arm processor for Windows PCs that does for PCs what Apple’s M-series chips did for Macs, promising both better battery life and better performance than equivalent Intel chips. This would be a departure from past Snapdragon chips for PCs, which have performed worse than (or, at best, similarly to) existing Intel options, barely improved battery life, and come with a bunch of software incompatibility problems to boot.

Early benchmarks that have trickled out look promising for the Snapdragon X. And there are other reasons to be optimistic—the Snapdragon X Elite’s design team is headed up by some of the same people who made Apple Silicon so successful in the first place.

Rumors indicate that Microsoft's flagship Surface tablet this year will switch to using Qualcomm's Arm chips exclusively rather than selling Arm and Intel versions alongside each other (an Intel Surface Pro 10 exists, but it's only sold to businesses). Microsoft has tried to make Arm Windows happen a bunch of times. But this time feels different.

A brief history of Arm Windows

The first public version of Windows to run on Arm processors was Windows RT, an Arm-compatible offshoot of Windows 8 that launched on a bare handful of devices back in late 2012.

Windows RT came with significant limitations, most notably a total inability to run traditional x86 Windows desktop apps—all apps had to come from the Microsoft Store, which was considerably more barren than it is today. There was no x86 compatibility mode at all.

That limitation may have been due in part to the limited, low-performance Arm hardware available at the time. Arm processors were still predominantly 32-bits, with slow processors and GPUs, 32 or 64GB of slow flash storage, and just 2GB of memory (at the time, 4GB was generally considered adequate for a PC, and 8GB was roomy). Even if you did have x86 app translation, translated apps would have felt awful since the Arm hardware already struggled to run the native built-in apps consistently well.

Advertisement

Windows RT died the death it deserved to die; it never ran on many devices, and those that did had totally vanished from the market by 2015 or so. But the technical underpinnings of the operating system remain relevant today.

As detailed by then-Windows head Steven Sinofsky, Microsoft did significant work to define a hardware abstraction layer (HAL), ACPI firmware, and basic class drivers for the Arm version of Windows so that the OS could install and run as expected on a wide variety of barely standardized Arm hardware the same way it did on a thoroughly standardized x86 PC. (Compare this to Google's Wild West approach to Android, which to this day can’t install basic OS or security updates without specific intervention from chipmakers and device manufacturers).

These were building blocks Microsoft could re-use for Windows 10, which first came to Arm devices in 2017 with support for 32-bit x86 app translation. This version of Windows-on-Arm also functioned more as a technical demo than the dawn of a new era, but it did come closer to becoming what Windows-on-Arm needed to be to succeed: a drop-in replacement for the x86 version of Windows, where the two versions were largely indistinguishable for non-technical users.

The next big step down that path came in 2020 when Microsoft announced a preview of 64-bit Intel app translation for Arm PCs, though the final version ended up being exclusive to Windows 11 when it launched in late 2021 (leaving behind, incidentally, that first wave of Windows 10 Arm PCs with a Snapdragon 835 processor in them—another case where early-adopting into this ecosystem has hosed users). Developers also got an easier on-ramp to Arm when Microsoft began allowing them to mix x86 and Arm code in the same app.

That brings us to where we are now: an Arm version of Windows that still has some compatibility gaps, especially around external accessories and specialized software. But the vast majority of productivity apps and even games will now run happily on the Arm version of Windows, with no user or developer intervention required.

Change is in the air

To figure out what Microsoft needs to do to make Arm PCs take off, it's instructive to look at Apple's switch from Intel's CPUs to its own M-series chips. Three big factors made the Apple Silicon switch so seamless and successful:

- Apple had an excellent compatibility layer for existing Intel apps in Rosetta 2.

- Apple's new chips were more power efficient and quite a bit faster than what Intel was offering at the time. This gave users some immediately noticeable benefits (namely better battery life) while also masking the performance impact of translating Intel apps.

- App developers were relatively quick to create Arm-native versions of their most important apps, making the increased speed of Apple Silicon chips even more noticeable. Within a year, almost all the apps I used day-to-day had made the switch. Today, a little over three years later, the only Intel-only apps I run into tend to be mostly unmaintained or barely maintained. This was important because while Apple's Rosetta translation looked good in benchmarks, in actual use, there was a minor but perceivable choppiness and lack of responsiveness that didn't exist in Arm-native apps.

Microsoft has mostly cracked the compatibility layer part of the equation, and it will actually be better than what Apple offers in some ways (Rosetta 2 never supported 32-bit Intel apps, for example, and Apple chose to foreclose the possibility by dropping 32-bit support on Intel Macs, too).

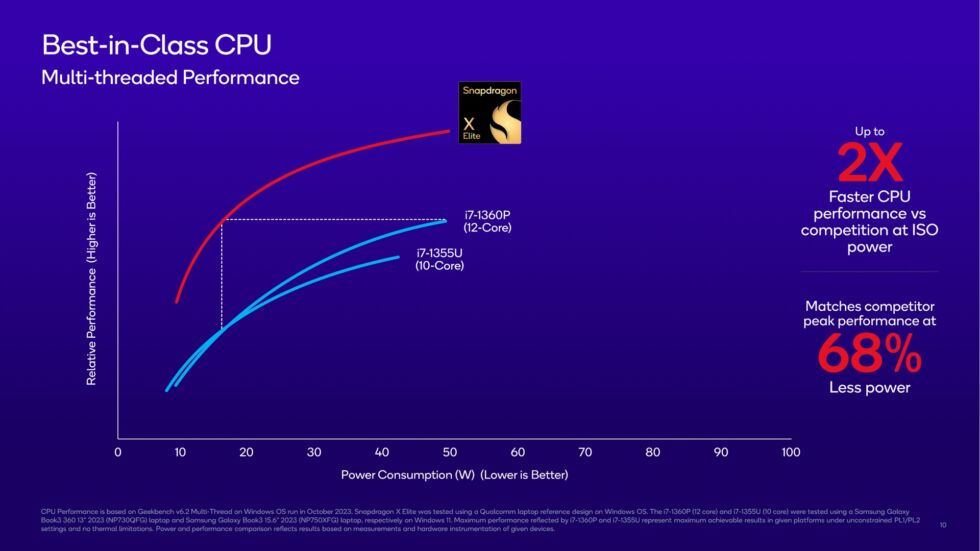

What's been missing so far is good hardware; to date, even the best of Qualcomm's chips have offered performance and battery life similar to Intel's or AMD's, and why would you put up with the compatibility downsides if there wasn't an upside? The Snapdragon X Elite promises to finally fix this, locking another key element into place.

Advertisement

That could still fall apart. We've seen a lot about the X Elite's speed and a lot of charts with bendy lines demonstrating the chips' power curve. But if Snapdragon X Elite laptops show up and they look and behave just like modern Intel and AMD laptops—noisy and hot under load, battery life that ranges from mediocre to merely decent—they'll still be a hard sell. But for now, I'm taking Microsoft's projected confidence as a sign that Qualcomm has finally cracked the hardware side of this.

Another thing that's different this time? Third parties are getting on board with Arm-native versions of their apps, a couple of years after Microsoft started pushing Arm-compatible versions of its dev tools more aggressively.

The most telling of the recent adopters is Chrome, easily the most important app that most people run on their PCs or Macs. Google began testing an Arm-native version of Chrome for Windows in January and released the stable version of the app in March.

The thing about Chrome is that Google goes where it thinks users will be; it doesn't want early adopters of a potentially popular platform to try to install Chrome, get frustrated for some reason, and bounce to something else.

When it looked like Windows 8 and its touchscreen interface would be a big deal, Google and Chrome were there. When Apple Silicon Macs launched, Google had an M1-native version of the app available within days of their launch. It's telling that now, of all times, after years and years without launching an Arm-native Windows browser, Google has gotten on board.

Recent improvements set the stage

In late 2022, I spent some time with the Arm version of Windows on Microsoft's "Windows Dev Kit 2023," which was literally the system board from the Arm version of the Surface Pro 9 inside a black plastic box. Formerly dubbed "Project Volterra" and sold for a relatively reasonable $600, the PC is intended to give developers a usable and reasonably performant Arm system to develop and test their apps on.

Even in 2022, I still ran into quite a few problems with apps that wouldn't install, hardware that didn't work because of unavailable drivers, and other rough edges that kept it from feeling like a "real" PC. But once the things that could be installed and configured were installed and configured, in day-to-day use as a browsing and writing machine, it felt remarkably unremarkable.

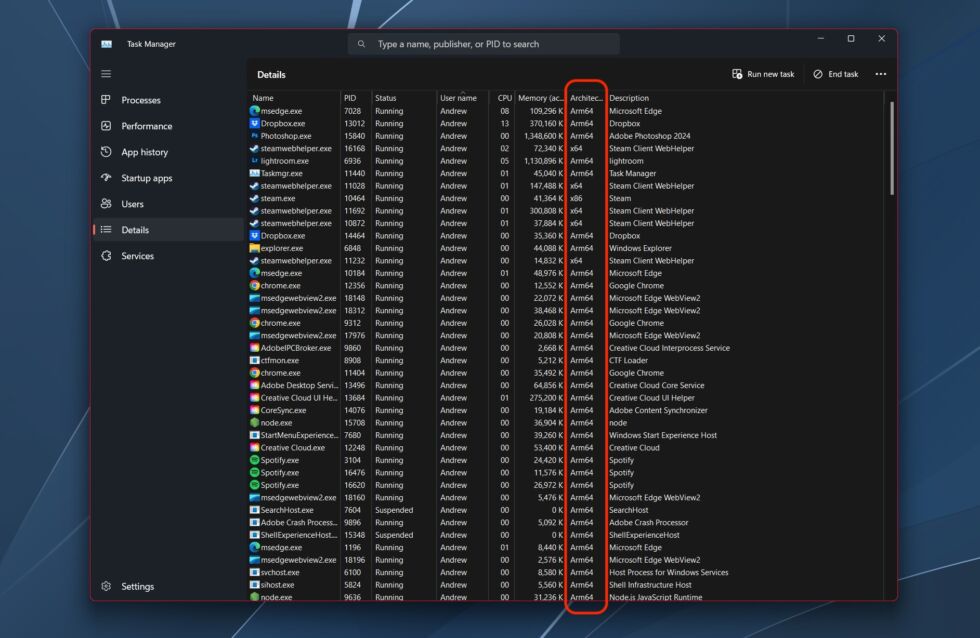

Things are even better now. The Dropbox client, not even installable 18 months ago, now has an Arm-native client that functions just fine. I had no problems downloading Adobe's Creative Cloud installer, which is an x86 file that seamlessly installed the Arm64 version of the Creative Cloud client and Arm64 versions of Photoshop and Lightroom. These were all things that caused mild-to-moderate headaches when trying to use this same computer not all that long ago.

I still ran into issues in instances where I wanted to install the Arm version of an app but got the x86 version by default instead. This still happens while downloading the Handbrake video encoding app from its website or the VLC player from either the Microsoft Store or VLC's website (the Arm64 version of VLC is still only available via unstable nightly builds, it seems). The x86 versions of these apps launch and run fine; you'll just have to deal with the app-translation performance penalty when you could be getting native performance instead.

AdvertisementAnd while it's nice to have Arm-native versions of apps like Chrome and Dropbox, they're still way outnumbered by the x86 apps. The native Slack and Discord clients are both x86, Steam is x86, all other Adobe apps are x86, major video and audio editing programs are all x86, and virtually all games are x86. You'll likely have trouble with any driver not built into Windows, as is still the case for my Focusrite USB mic preamp.

Some of these problems are ignorable in the short term because of the x86 compatibility layer. Slack and Discord run OK on the Snapdragon 8cx Gen 3/Microsoft SQ3, and they'll run better on the X Elite. A lot of games just work, and Qualcomm seems confident that even recent-ish AAA titles will run fine (the company demoed Baldur's Gate 3 and Control in a recent tech session).

But some barriers will be impossible to surmount without attention from developers. Games with any kind of anti-cheat system almost never work with any kind of translation layer. Drivers will need to be written or recompiled. But that kind of work won't start happening before the user base is there, and the user base won't be there until there are (1) concrete benefits to using Arm hardware and (2) broad compatibility for bread-and-butter apps like Chrome.

Both of those problems could finally be solved this year. It's still not guaranteed to lead to first-class Windows-on-Arm support from major game makers, but if we see something like Fortnite or Overwatch 2 pick up Arm Windows support, it will be a major sign that the tide is turning.

An actually viable Arm Windows is good for everyone

We've talked about this hypothetical turning point of Windows-on-Arm mostly in the context of new Snapdragon X Elite PCs, but a healthier Arm ecosystem for Windows would benefit many different people, whether they wanted to buy a new PC or not.

AdvertisementSome of this is "rising tide lifts all boats"-type stuff, where Windows-on-Arm hardware like 2019's original Surface Pro X or this weird $200 Best Buy laptop will actually get better, faster, and more usable as native Arm versions of apps become more plentiful.

But it's also valuable outside of the Windows ecosystem. The experience of using Windows via Parallels on an Apple Silicon Mac, for example, is getting pretty close to the way it used to be on Intel Macs, outside of specific things like being unable to run newer DirectX 12 games. We'll probably never see a version of Windows that can run directly on the hardware, as was possible in the Intel days—the odds of Apple releasing and maintaining its own Windows drivers are near or possibly even below zero—but lack of Windows compatibility was a pain point for Apple Silicon Macs just a few years ago.

There's also the possibility of a better hardware ecosystem. If Arm PCs begin selling in significant numbers, we might see companies like Samsung, Nvidia, MediaTek, or Arm itself take more of an interest in high-performance Arm chips for PCs. Microsoft and Qualcomm have allegedly had some kind of often-implied, rarely talked-about exclusivity agreement for the Arm versions of Windows 10 and Windows 11, though various rumors have also reported that it has expired or is expiring soon. One of the reasons to root for the Arm transition is to give us, the PC buyers of the world, options beyond what Intel or AMD are doing. More options beyond what Qualcomm is doing would be even better.