It's well-known that the ancient Maya had their own version of ball games, which were played with a rubber ball on stone courts. Such games served not just as athletic events but also religious ones that often involved ritual sacrifices. Archaeologists have now found evidence that the Maya may have blessed newly constructed ball courts in rituals involving plants with hallucinogenic properties, according to a new paper published in the journal PLoS ONE.

“When they erected a new building, they asked the goodwill of the gods to protect the people inhabiting it,” said co-author David Lentz of the University of Cincinnati. “Some people call it an ensouling ritual, to get a blessing from and appease the gods.” Lentz and his team previously used genetic and pollen analyses of the wild and cultivated plants found in the ancient Maya city Yaxnohcah in what is now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, revealing evidence of sustainable agriculture and forestry spanning a millennia.

As we've reported previously, there is ample evidence that humans in many cultures throughout history used various hallucinogenic substances in religious ceremonies or shamanic rituals. That includes not just ancient Egypt but also ancient Greek, Vedic, Maya, Inca, and Aztec cultures. The Urarina people who live in the Peruvian Amazon Basin still use a psychoactive brew called ayahuasca in their rituals, and Westerners seeking their own brand of enlightenment have also been known to participate.

Last year, archaeologists found that an ancient Egyptian vase in the shape of the deity Bes showed traces of chemical plant compounds known to produce hallucinations. Specifically, they identified Syrian rue (Peganum harmala), whose seeds are known to have hallucinogenic properties that can induce dream-like visions, per the authors, thanks to its production of the alkaloids harmine and harmaline. There were also traces of blue water-lily (Nymphaea cerulea), which contains a psychoactive alkaloid that acts as a sedative; it's one of several candidate plants that scholars believe might be the fruit of the lotus tree described in Homer's Odyssey. Members of the cult of Bes may have consumed a special cocktail containing the compounds to induce altered states of consciousness.

AdvertisementAnd in 2022, archaeologists uncovered evidence that an ancient Peruvian people laced the beer served at their feasts with hallucinogens. Excavations at a remote Wari outpost called Quilcapampa unearthed seeds from the vilca tree that can be used to produce a potent hallucinogenic drug. The seeds, bark, and other parts of the tree all contain DMT, a well-known psychedelic substance that is also found in the ayahuasca brews of Amazonian tribes. However, the primary active ingredient is bufotenine. There is also evidence from historical accounts that a juice or tea derived from vilca seeds was sometimes added to chicha, a fermented beverage made from maize or the fruits of the molle tree native to Peru.

The people of the neighboring state of Tiwanaku were known to mix such hallucinogens with alcohol, specifically maize beer. However, the Wari likely used these substances to help forge political alliances and expand their empire. It's possible the Wari held one big final blowout before the site was abandoned. The Wari empire lasted from around 500 CE to 1100 CE in the central highlands of Peru.

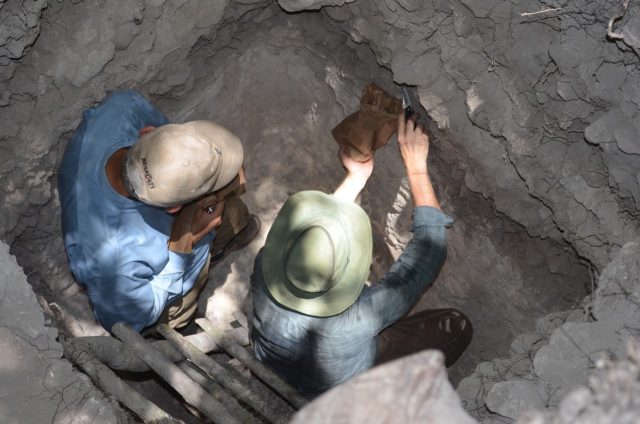

This latest study stems from soil samples taken during excavations from 2016 to 2022 at Yaxnocah, nine or so miles north of the Guatemalan border—specifically from a stone and earthen ball court platform linked by a causeway to a nearby ceremonial complex. Some 300 such ball courts have been found in the highlands of Guatemala and Chiapas, most dating to the post-classic period.

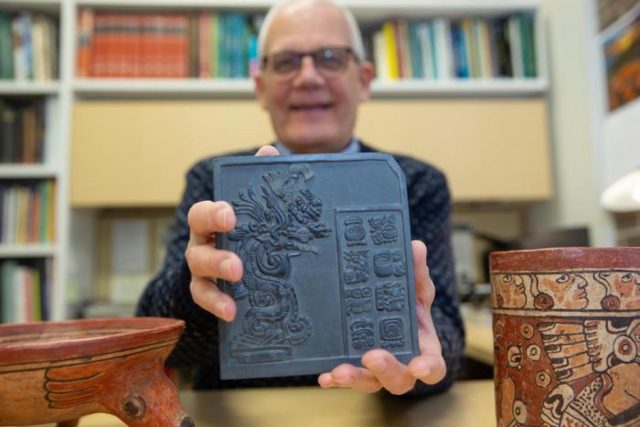

Much of what we know about these games comes from Maya murals, carvings, and other decorative artifacts. One game, known as pok-a-tok, had rules similar to soccer or basketball, with the goal of trying to get the ball through a carved stone ring or hoop mounted on a wall. But with Maya ball games, there were also ritual human sacrifices by decapitation or disembowelment—possibly of the winning team's captain. The courts themselves were typically I-shaped, with a long middle field and parallel ends, as well as raised platforms on either side for spectators. Painted murals surrounded the ball courts, and arenas were typically decorated movable stone markers (hacha).

The Yaxnocah ball court platform had originally supported several Middle Preclassic (1000–400 BCE) domestic structures, per the authors, later remodeled to add the ball court sometime between 400 BCE and 200 CE. In such cases, a blessing ritual would be performed that often involved offerings of ceramics or jewelry, according to co-author Nicholas Dunning. “We have known for years from ethnohistorical sources that the Maya also used perishable materials in these offerings, but it is almost impossible to find them archaeologically, which is what makes this discovery using environmental DNA (eDNA) so extraordinary,” he said.

The primary difficulty is that tropical climates mean that plants decompose so quickly that no traces of them remain millennia later. There have been some exceptions, such as at a site in El Salvador where a volcanic eruption covered a Maya village with ash, or cave sites where plant remains were preserved in ceramic vessels. The use of eDNA technology can augment the traditional paleobotanical toolkit, per the authors, having previously used the method to analyze samples taken from both Yaxnohcah and the Maya city of Tikal.

The authors recorded over 105,000 gene sequences, mostly from bacteria or fungi, but 15 were from plants, four of which the team was able to identity at the genus or species level. Each of those four "has special properties that would have made them a likely component of an ancient ritual," the authors wrote. "Together, they form an intriguing set of medicinal and ceremonial plants whose combination elicits questions about symbolic meaning and religious associations."

Advertisement

The most intriguing was a type of morning glory vine called xtabentum; today, the Maya brew mead from honey made by bees that feed on pollen from xtabentum flowers. The Aztecs called it coaxihuitl ("snake plant") and the seeds are known to contain alkaloids with d-lysergic acid amide and d-lysergic acid methylcarbinolamide—compounds with a similar structure to LSD and alkaloids present in ergot fungi. The Aztecs used these hallucinogenic seeds in divination ceremonies meant to communicate with their gods. How the ancient Maya may have used xtabentum in their rituals is more vague, but Lentz et al. have found evidence in the ethnographic literature, such as the Dresden Codex, that their usage was similar to that of the Aztecs.

The analysis also revealed traces of chili peppers in the nightshade family, a common condiment or flavoring among the Maya and many other Old World cultures. Modern Maya use chili pepper seeds as treatments for a variety of conditions and for certain religious ceremonies. Traces of jool, a small tree with medicinal properties, indicates that the xtabentum and other plants may have been wrapped in bark and leaves, a common practice for ceremonial food bundles. Finally, there were traces of lancewood (chilcahuite), a tree whose wood is used to make spears and archery bows, as well as having medicinal properties.

"The Maya are known to place healing bundles below floors as a protective measure to ward off external causes of illness," the authors concluded. "An even stronger possibility, however, was that this was part of an ensouling or fixed earth ritual... Finally, this assemblage of plants may have been part of a divination ritual... Whatever the intent of the Maya petitioners, it seems clear that some kind of divination or healing ritual took place at the base of the ball court during the Late Preclassic period."

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2024. 10.1371/journal.pone.0301497 (About DOIs).