HOUSTON—While it doesn't have the same relevance to public consciousness as safety problems with commercial airliners, a successful test flight of Boeing's Starliner spacecraft in May would be welcome news for the beleaguered aerospace company.

This will be the first time the Starliner capsule flies into low-Earth orbit with humans aboard. NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams are in the final stages of training for the so-called Crew Flight Test (CFT), a milestone running seven years behind the schedule Boeing said it could achieve when it won a $4.2 billion commercial crew contract from NASA a decade ago.

If schedules hold, Wilmore and Williams will take off inside Boeing's Starliner spacecraft aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket after midnight May 1, local time, from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. They will fly Starliner to the International Space Station for a stay of at least eight days, then return the capsule to a parachute-assisted, airbag-cushioned landing in the western United States, likely at White Sands, New Mexico.

A shakeup at Boeing

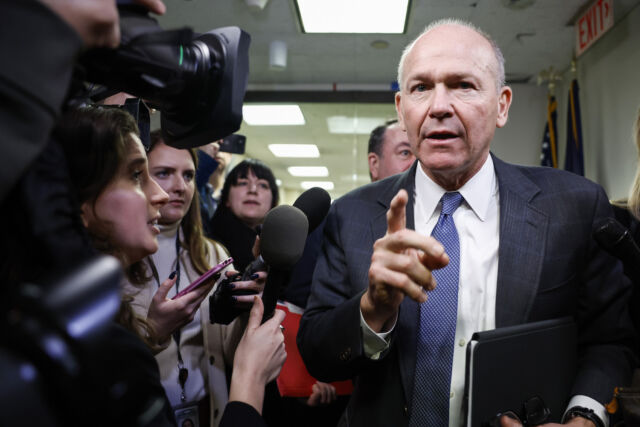

The first human spaceflight with Starliner will launch under a lame-duck Boeing CEO. Dave Calhoun, who took the helm at Boeing in 2020, announced Monday he will step down at the end of the year. Boeing's chairman, Larry Kellner, will not seek reelection at the company's next shareholder meeting. Effective immediately, Boeing is also replacing the head of its commercial airplanes unit.

AdvertisementThe last few years have not been good for Boeing. A spate of safety shortcomings in the company's commercial airline business has shattered the company's reputation. Two crashes of Boeing's 737 Max 8 airplanes in 2018 and 2019 killed 346 people, and investigators blamed Boeing's design and software for the accidents.

Probes into those accidents revealed Boeing cut corners and hid flaws from regulators and pilots in its design of the 737 Max, meant to keep the company competitive with new-generation airplanes produced by its European rival Airbus. Then, in January, a door plug on an Alaska Airlines 737 Max 9 airplane blew out in flight, causing a rapid decompression and forcing an emergency landing.

Everyone onboard survived, but the incident triggered a government investigation that revealed bolts meant to hold the door plug to the side of the airplane were missing. The bolts were apparently missing when the new 737 Max 9 left Boeing's factory last year, and the chair of the National Transportation Safety Board reported earlier this month that Boeing has no records of the work to install the door plug.

In a report released by the Federal Aviation Administration last month, a panel of experts found that Boeing's safety culture was "inadequate and confusing." The panel also noted a "lack of pilot input in aircraft design and operation."

Don’t expect perfection

Starliner, too, has not been immune from technical problems, oversights, and delays. Wilmore, Starliner's first commander, told Ars he is not worried about troubles in Boeing's airplane division spilling over to the Starliner program.

"Those don’t cross," Wilmore said in an interview with Ars. "They may have some engineering expertise where they cross, but they’ve got people working the space part, and they’ve got people working (airplanes)."

Boeing runs its commercial airplane business as a separate division from the units that build spacecraft or military aircraft. But the company has tried to lump these unrelated programs together before. In 2015, Boeing announced the establishment of an organization to manage the development of two of its flagship space projects—Starliner and NASA's Space Launch System rocket—alongside the 777X commercial airplane, the Air Force's KC-46 refueling tanker, and the next-generation Air Force One presidential aircraft.

At the time, Boeing said the new organization, patterned on commercial airplane development, would help "break the cost curve" on these programs. It would also allow the company to "more effectively apply engineering expertise, development program best practices, and program management and integration from across Boeing to our most important development activities."

Several of these programs have been financial losers for Boeing. The company has taken $2.4 billion in losses on its fixed-price contract with the Air Force to convert two 747s into presidential transports and more than $7 billion in charges on the Air Force's KC-46 tanker program, which is also based on a fixed-price contract. To date, Boeing is $1.4 billion in the red on the Starliner program.

In contrast, Boeing's SLS contract with NASA is a cost-plus arrangement, meaning the contractor is not on the hook for cost overruns. Instead, the financial risk is transferred to US taxpayers. The Boeing-built SLS core stage, while costly, behind schedule, and expendable, performed almost perfectly on NASA's Artemis I test flight in 2022, a precursor to future human flights to the Moon.

Advertisement"There’s a culture in any company, any organization, that is set from the higher-up," Wilmore said. "So there’s some of that, but there’s none of that from the other part (commercial airplanes) that I would say is ... even a consideration (for Starliner)."

Wilmore and Williams are used to taking calculated risks. Both are veteran US Navy test pilots, and each has flown to space twice before.

“We wouldn't be sitting here if we didn't feel, and tell our families that we feel, confident in this spacecraft and our capabilities to control it," Williams said in a press conference Friday.

While the astronauts are confident in Starliner's safety, this mission's purpose is to wring out any problems before Boeing and NASA declare the spacecraft ready for operational service.

"The expectation from the media should not be perfection," Wilmore said. "This is a test flight. Flying and operating in space is hard. It’s really hard, and we’re going to find some stuff. That’s expected. It’s the first flight where we are integrating the full capabilities of this spacecraft."

Outside observers, Wilmore said, "don’t realize that there are flights going on with F-18s back in the day, or the T-45s that I flew, where we found stuff and fixed it."

"You don’t get visibility in those programs and those flights," he said. "This one is visible, especially with some of the things that have transpired. So don’t have that expectation, please. It’s not going to be perfect. But it’s not going to be bad, either. We wouldn’t go if we thought that ... It’s going to be things that are rectifiable. And the whole thing is to get up, get to the space station, and get back, and we’re going to show that it has that capability.”

Certifying for crew

The test flight is a final step before NASA formally approves Starliner for regular six-month crew rotation flights to the space station, each carrying four astronauts. SpaceX, NASA's other commercial crew contractor, has provided this service since 2020.

With Starliner, NASA will have two human-rated orbital spaceships available at the same time, something the agency has never had before. Getting Starliner online will also reduce NASA's reliance on Russia's Soyuz as a backup option for crew transportation.

Steve Stich, NASA's commercial crew program manager, said Friday that the space agency is in the "final cusp" of certifying and human-rating the Starliner spacecraft for the upcoming astronaut test flight. Engineers have data from two unpiloted Starliner test flights, a launch abort demonstration, and extensive ground testing that show the spacecraft should meet NASA's safety standards.

“From my perspective, so far, it seems like we’ve looked at everything," Stich said. "We’ve done, in many cases, independent analysis, which we do the same thing for (SpaceX's) Dragon relative to landing loads, abort performance, rendezvous and docking, all those sorts of things."

Getting to this point has been a slog for Boeing and NASA. The first orbital test flight of Starliner in 2019, without a crew inside, ended prematurely after a software problem caused its mission clock to have the wrong time. This caused the capsule to burn more fuel than expected after arriving in space, preventing it from reaching the space station.

Corroded valves inside Starliner's propulsion system caused another delay in 2021 when Boeing was about to launch a redo of the troubled 2019 test flight. Finally, in May 2022, Boeing successfully launched and docked a Starliner spacecraft at the International Space Station, then returned the capsule to Earth.

Engineers addressed relatively minor problems with thrusters and Starliner's cooling system discovered on the 2021 test flight, and Boeing appeared to be on track to launch the Crew Flight Test last summer. But like a game of whack-a-mole, preflight readiness reviews uncovered more problems with Starliner's parachutes and the presence of flammable tape inside the spacecraft, prompting another delay of nearly a year.

Advertisement“We can safely say those issues are behind us," said Mark Nappi, Boeing's Starliner program manager.

NASA and Boeing officials took this extra time to complete additional integrated software testing, and introduce an upgraded parachute design that previously was not supposed to fly on Starliner until a later mission.

Stich said the agency has close oversight of Boeing on the Starliner program.

"We had people side by side inspecting the tape, inspecting the wiring after the tape was removed, making sure that was done properly, same thing with parachutes. So, the process is a little different than aviation," he said. "We’re talking two spacecraft that are going to fly multiple missions. So a lot individual care and feeding goes into every single one of those spacecraft, and NASA is side by side with Boeing.”

NASA is still reviewing data on Boeing's redesigned parachutes, although Stich said the last parachute test "gave us a heck of a lot of confidence in that system." NASA is also completing an independent analysis of the Starliner's launch abort system, but like the parachutes, Stich said he expects to finalize the agency's approval of that system by April.

"The chief engineers are now sitting down with every single one of their disciplines to ask those very questions. Have we missed something? Are you worried about something? Do you think there’s an area we need to do a little more work in?" Stich said.

Meanwhile, Boeing technicians at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida are loading the Starliner spacecraft with propellants ahead of its target launch date of May 1. This is the same crew capsule that flew into orbit on the unpiloted test flight in 2019. Once fueling is complete, ground teams will transfer the capsule from Boeing's factory around April 10 over to a vertical hangar at ULA's launch pad a few miles away at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, where ULA will lift it atop the already-assembled Atlas V rocket.

Assuming all these milestones go off without a hitch, the Atlas V will roll out to its launch pad a couple of days before liftoff. Then, late on April 30, Wilmore and Williams will put on their solid blue pressure suits and strap into Starliner for launch at 12:55 am EDT (04:55 UTC) on May 1.