True wine aficionados might turn up their noses, but canned wines are growing in popularity, particularly among younger crowds during the summer months, when style often takes a back seat to convenience. Yet these same wines can go bad rather quickly, taking on distinctly displeasing notes of rotten eggs or dirty socks. Scientists at Cornell University conducted a study of all the relevant compounds and came up with a few helpful tips for frustrated winemakers to keep canned wines from spoiling. The researchers outlined their findings in a recent paper published in the American Journal of Enology and Viticulture.

“The current generation of wine consumers coming of age now, they want a beverage that’s portable and they can bring with them to drink at a concert or take to the pool,” said Gavin Sacks, a food chemist at Cornell. “That doesn’t really describe a cork-finished, glass-packaged wine. However, it describes a can very nicely.”

According to a 2004 article in Wine & Vines magazine, canned beer first appeared in the US in 1935, and three US wineries tried to follow suit for the next three years. Those efforts failed because it proved to be unusually challenging to produce a stable canned wine. One batch was tainted by "Fresno mold"; another batch resulted in cloudy wine within just two months; and the third batch of wine had a disastrous combination of low pH and high oxygen content, causing the wine to eat tiny holes in the cans. Nonetheless, wineries sporadically kept trying to can their product over the ensuing decades, with failed attempts in the 1950s and 1970s. United and Delta Airlines briefly had a short-lived partnership with wineries for canned wine in the early 1980s, but passengers balked at the notion.

The biggest issue was the plastic coating used to line the aluminum cans. You needed the lining because the wine would otherwise chemically react with the aluminum. But the plastic liners degraded quickly, and the wine would soon reek of dirty socks or rotten eggs, thanks to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide. The canned wines also didn't have much longevity, with a shelf life of just six months.

AdvertisementThanks to vastly improved packing processes in the early 2000s, canned wine seems to finally be finding its niche in the market, initially driven by demand in Japan and other Asian markets and expanding after 2014 to Australia, New Zealand, the US, and the UK. In the US alone, projected sales of canned wines are expected to grow from $643 million in 2024 to $3.12 billion in 2034—a compound annual growth rate of 10.5 percent.

Granted, we won't be seeing a fine Bordeaux in a can anytime soon; most canned wine comes in the form of spritzers, wine coolers, and cheaper rosés, whites, or sparkling wines. The largest US producers are EJ Gallo, which sells Barefoot Refresh Spritzers, and Francis Ford Coppola Winery, which markets the Sofia Mini, Underwood, and Babe brands.

There are plenty of oft-cited advantages to putting wine in cans. It's super practical for picnics, camping, summer BBQs, or days at the beach, for example, and for the weight-conscious, it helps with portion control, since you don't have to open an entire bottle. Canned wines are also touted as having a lower carbon footprint compared to glass—although that is a tricky calculation—and the aluminum is 100 percent recyclable.

This latest study grew out of a conference session Sacks led that was designed to help local winemakers get a better grasp on how best to protect the aromas, flavors, and shelf life of their canned wines since canned wines are still plagued by issues of corrosion, leakage, and off flavors like the dreaded rotten egg smell. “They said, ‘We’re following all the recommendations from the can suppliers and we still have these problems, can you help us out?’” Sacks said. “The initial focus was defining what the problem compounds were, what was causing corrosion and off aromas, and why was this happening in wines, but not in sodas? Why doesn’t Coca-Cola have a problem?”

So he partnered with fellow Cornell food scientist Julie Goddard, who specializes in packaging and material science, to characterize the chemical makeup of commercial canned wines. They sampled a broad range of samples wth different internal coatings, storing them for up to eight months. They placed another batch in incubator ovens to accelerate aging over one to two weeks and even created their own canned wine, using compounds they suspected were problematic.

Most of the compounds they measured had little to no correlation with the issues confronting canned wines. The strongest correlation was for a molecular form of sulfur dioxide (SO2), used as an antioxidant and antimicrobial in wine production. The SO2 reacts with aluminum to produce hydrogen sulfide, and the plastic liners could not fully prevent that interaction from occurring within four to six months of packaging.

Based on these findings, Sacks et al. recommended wine makers keep molecular SO2 to 0.4 parts per million (ppm); standard practice is usually 0.5 to 1 ppm. (Most red wines already have lower SO2 levels, but red wines aren't typically packaged in cans.)

“We’re suggesting that wineries aim on the lower end of what they’re usually comfortable with,” said Sacks. “Yes, there’s going to be the chance of having more issues of oxidation. But the good news is that cans provide a hermetic seal. They’re not likely to let in any air if the canning is done properly, which is why brewers love them. It’s great for preventing oxidation.”

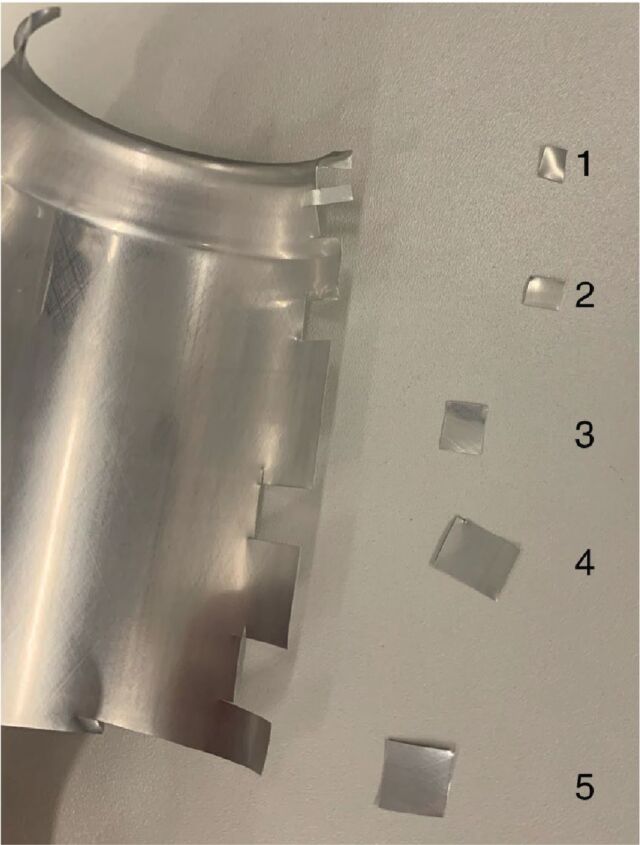

AdvertisementA follow-up experiment looked specifically at how different kinds of can liners affected the formation of hydrogen sulfide, given the reported variation by winemakers. Epoxy liners can also help extend the shelf life of canned wines, and the thicker the coating, the less corrosion is likely to occur. The tradeoff is higher cost and a less environmentally friendly product. Sacks and Goddard are now working with Cornell chemist Hector Abruna to design better liners using corrosion-resistant food-grade materials.

Of course, wineries will still have to contend with overcoming consumer reluctance and lingering snobbery over alternative packaging. (Boxed wine, despite its growing popularity, is also viewed as decidedly subpar by many wine lovers.)

Back in 2017, Washington Post reporter Dave McIntyre sampled a few canned wines, drinking straight from the can, pouring it into a plastic cup, and pouring it into a bona fide wine glass to compare how the vessel impacted the taste. He found that the wine tasted progressively better with each iteration, best of all when poured into a glass. It seems even canned wines need to breathe a little. This, McIntyre noted, defeats the convenience of buying canned wine in the first place, but it's still a handy trick. Or you can just kick it old school and stick with traditional corked bottles, perhaps investing in one of those fancy wine picnic cooler bags for good measure.

DOI: American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 2024. 10.5344/ajev.2023.23069 (About DOIs).

Listing image by BackyardProduction/Getty Images