The US Department of Agriculture this week posted an unpublished version of its genetic analysis into the spillover and spread of bird flu into US dairy cattle, offering the most complete look yet at the data state and federal investigators have amassed in the unexpected and worrisome outbreak—and what it might mean.

The preprint analysis provides several significant insights into the outbreak—from when it may have actually started, just how much transmission we're missing, stunning unknowns about the only human infection linked to the outbreak, and how much the virus continues to evolve in cows. The information is critical as flu experts fear the outbreak is heightening the ever-present risk that this wily flu virus will evolve to spread among humans and spark a pandemic.

But, the information hasn't been easy to come by. Since March 25—when the USDA confirmed for the first time that a herd of US dairy cows had contracted the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus—the agency has garnered international criticism for not sharing data quickly or completely. On April 21, the agency dumped over 200 genetic sequences into public databases amid pressure from outside experts. However, many of those sequences lack descriptive metadata, which normally contains basic and key bits of information, like when and where the viral sample was taken. Outside experts don't have that crucial information, making independent analyses frustratingly limited. Thus, the new USDA analysis—which presumably includes that data—offers the best yet glimpse of the complete information on the outbreak.

Undetected spread

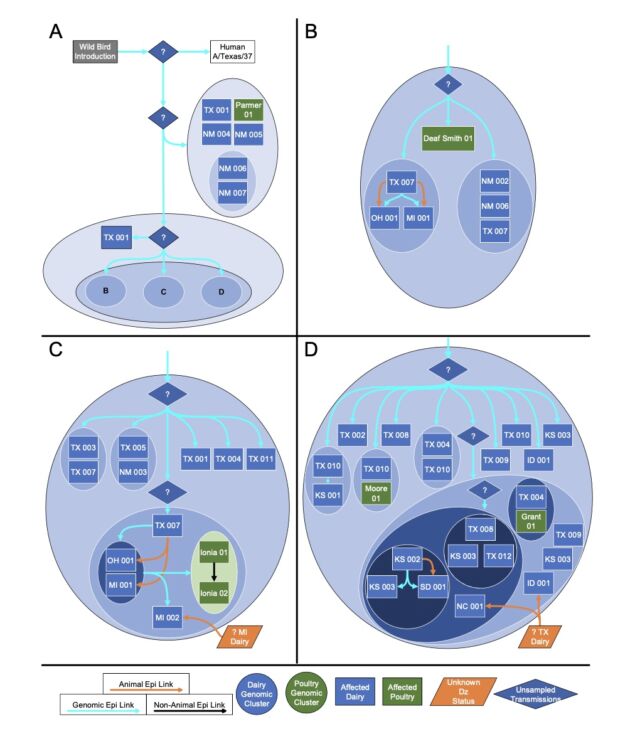

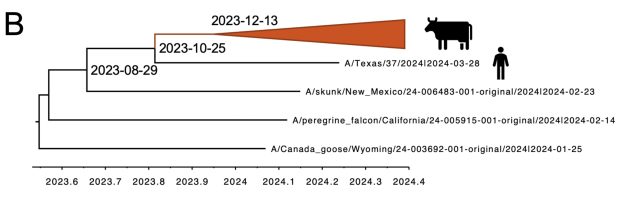

One of the big takeaways is that USDA researchers think the spillover of bird flu from wild birds to cattle began late last year, likely in December. Thus, the virus likely circulated undetected in dairy cows for around four months before the USDA's March 25 confirmation of an infection in a Texas herd.

AdvertisementThis timeline conclusion largely aligns with what outside experts previously gleaned from the limited publicly available data. So, it may not surprise those following the outbreak, but it is worrisome. Months of undetected spread raise significant concerns about the country's ability to identify and swiftly respond to emerging infectious disease outbreaks—and whether public health responses have moved past the missteps seen in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But another big finding from the preprint is how many gaps still exist in our current understanding of the outbreak. To date, the USDA has identified 36 herds in nine states that have been infected with H5N1. The good news from the genetic analysis is that the USDA can draw lines connecting most of them. USDA researchers reported that "direct movement of cattle based upon production practices" seems to explain how H5N1 hopped from the Texas panhandle region—where the initial spillover is thought to have occurred—to nine other states, some as far-flung as North Carolina, Michigan, and Idaho.

"We cannot exclude the possibility that this genotype is circulating in unsampled locations and hosts as the existing analysis suggests that data are missing and undersurveillance may obscure transmission inferred using phylogenetic methods," the USDA researchers wrote in their preprint.

The anomalous human case

Based on the circumstances, it would be easy to assume that the man was infected via exposure to those animals, and the virus in his eye would closely match what was seen in cattle in the area. Except it doesn't. The virus isolate is related to the clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI H5N1 virus sequences from cows in the area, but it is an outlier, containing genetic differences that prevent it from clustering in phylogenetic analyses with all the other cattle isolates.

And the cows with which the man had contact were potentially never sampled. In an email to Ars, a spokesperson for the USDA said that the agency "does not have information about the herd associated with the reported human exposure case." The agency declined to answer why they didn't have that information.

AdvertisementOn Friday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a case study of the man's H5N1 eye infection in the New England Journal of Medicine. In a supplementary appendix to the study, CDC researchers acknowledged, too, that the "Sequence data from the farm where the infected dairy farm worker was exposed to presumably infected cattle was not available." The CDC did not respond to a follow-up question from Ars on why that data is not available. But, USDA and CDC officials have previously noted that some farmers and farm workers have not allowed health investigators to conduct testing.

With only the genetic analyses to go on, the man's H5N1 infection appears anomalous and leaves open two possibilities as to how it happened: There were two separate spillover events from wild birds to cows, and the man's case is part of a separate transmission chain, or there was only one spillover, but the virus sequences split, and the man was infected with a second branch that either died out or is yet unsampled.

When looking at only the cattle genetic sequences, the USDA researchers reported in their preprint that it looks like there was only one spillover event, an event in December in the Texas panhandle that links to all of the cattle infections. "These data support a single introduction event from wild bird origin virus into cattle, likely followed by limited local circulation for approximately 4 months prior to confirmation by USDA," the researchers wrote.

A second spillover?

However, based on the human case, a second spillover is possible, according to Tom Peacock, an influenza virologist at The Pirbright Institute, a British research institute focused on the study and control of infectious diseases in farm animals. "I'm not convinced from the current data we can yet infer if the human case was the same spillover or not," he told Ars.

In the appendix to its case study, the CDC agreed with Peacock's assessment.

Based on these analyses, it is possible the human was infected with an earlier, slightly different virus that was circulating in cattle prior to an evolutionary bottleneck that occurred in a small number of herds in the Texas panhandle, which subsequently seeded the expansion of the phylogenetic group that has now spread to multiple US states. Alternatively, it is possible that there was more than one independent spillover of wild bird virus into cattle in the US that gave rise to genetically different, albeit closely related, B3.13 genotype viruses in cattle.

The CDC added that it did believe the person was infected via cows, not wild birds or another secondarily infected mammal.

Virologist Angela Rasmussen, an expert in emerging infectious diseases at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan, agreed with the assessment. "[I]t does seem like the most likely explanation is that it was from a cow," Rasmussen told Ars. "That fits with what has become very apparent about this outbreak: it's incredibly undersampled and much bigger than we currently have been able to quantify. To really understand this, we need to really increase sampling and surveillance as well as increase the number of sequences available for these analyses."

So far, the genetic surveillance isn't comforting. The USDA researchers in their preprint noted that from the sequences available, it's clear that the virus is continuing to accrue new genetic changes, including mutations in some places of the genome that are associated with adaption to spreading in mammals. There were also a small number of variants lurking among the cattle, they note. "If these low-frequency variants become dominant, they may have phenotypes that increase the probability of interspecies transmission," the USDA researchers warned.

AdvertisementCall for more surveillance

Overall, the analysis highlights the need for far more H5N1 surveillance, sampling, and sequencing—something experts are calling for. At this point, it may be too late to fill the gaps that occurred early on in the outbreak, Peacock told Ars. In particular, we may never really know how the human case became infected. "I don't know if those gaps will be able to be retrospectively filled," he said. If sampling of the cows wasn't done around the time of the infection, it may be too late, he explained.

The CDC reported additional hurdles to surveilling the man's infection in today's case report. The CDC would have liked to collect follow-up swabs from the man to assess viral levels and the duration of viral shedding. But they weren't able to collect that data. They were also unable to collect blood samples from the man and his household contacts to look for antibodies that would mark exposure to the H5N1 virus.

The man's case has worrying features, Rasmussen noted to Ars. The man had conjunctivitis but no respiratory symptoms, which one might otherwise expect from an influenza infection. The CDC noted that the man wore gloves while working with cows, but did not have eye or respiratory protection.

"This might suggest a different route of transmission and also implies that there may be other, unrecognized human cases," Rasmussen said. "That worries me a lot, because if there are human cases that are unrecognized because they are clinically different than the lethal pneumonia people expect from H5N1, that provides more opportunities for the virus to adapt to a human host." The fact that farm workers may be from vulnerable segments of the population, including undocumented workers, means they may lack access to healthcare, making it all the harder to detect cases.

In a press briefing Wednesday, Demetre Daskalakis, director of CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said that states are monitoring over 100 people for symptoms after presumed exposure to H5N1, but only around 25 people have been tested for the virus so far.

"It would not surprise me at all to learn that there are more human cases that are undetected for all these reasons," Rasmussen said. "Unfortunately, I can’t think of a way to evaluate this, short of other human cases being recognized and reported by public health officials."